Eugene O’Neill – ‘Long Day’s Journey into Night’

Plays, eh? The last time I went to theatre was to see Sweet Bird of Youth, a month or two ago, and I would have written about it here, but oh man, it was depressing. Suspicious and malicious, characters tearing themselves apart, and nowhere for the audience to invest any sympathy. The thing that gets me is the assumption that bad circumstances and an emotional (or just shouty) rendition of them will produce something of interest. I’ve a friend who, when he first went to University, couldn’t move for people wanting to confide that they were on Prozac: ‘Look at me! I’m fucked up!’ It’s a way of forcing civility, I suppose, and even encouraging a return performance of circumstantial affection. A lot of plays do the same thing. Unlike a novel, which can take its time and wind its way into your heart over the course of a few weeks, a play has two, three hours, so it has to up the histrionics. That’s the negative way of putting it, and when these mundane kind of tensions are apparent from the audience, something has gone wrong. When they are not, the directness of the medium is all in its favour.

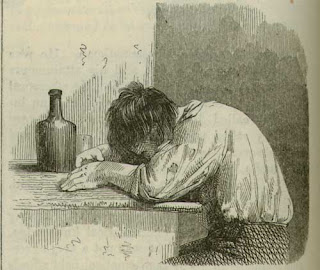

Long Day’s Journey into Night reads like it would work. Presumably it has a track record of doing so, but I don’t know anything about that (I picked it up because Kevin Spacey made his new A Moon for the Misbegotten sound tantalising on the radio the other week, and because Kevin Rowland lists Eugene O’Neill in ‘Burn it Down’ in a righteous way). In it, nothing good happens. The lives of the family it dramatises are in what would seem to be a steep and permanent decline. They grumble about each other, they drink to excess, one of them (youngest son Edmund) is dying of TB but drinks large quantities of whiskey regardless (conjuring an anatomically incorrect image of alcohol eating into brittle lungs), and the mother Mary (ha ha) is a morphine addict. The father is disliked by all for being rich but miserly, a fact which is blamed upon his own father’s abandonment of his mother when he was still a small boy, and the poverty which ensued. His children and his wife blame all their ills on this miserliness, which is unnecessary as James Tyrone has become rich as a popular if unfulfilled actor. He flinches when someone leaves a light on unnecessarily, keeps tabs on the level of the whiskey in the bottle, and tries to get Edmund treated as cheaply as possible. He’s as tight as they come, but he’s not entirely a monster.

All the ‘Woe is me’ buttons are pressed, in other words. It should be depressing as hell, but it isn’t. Reading the play, the first thing that strikes you is the length of the stage directions at the beginning of Act One. They are incredibly detailed, not only regarding the layout of the room, but even the layout of the actors’ faces:

Mary is fifty-four, about medium height. She still has a young, graceful figure, a trifle plump, but showing little evidence of middle-aged waist and hips, although she is not tightly corseted. Her face is distinctly Irish in type. It must once have been extremely pretty, and is still striking. It does not match her healthy figure but is thin and pale with the bone structure prominent. Her nose is long and straight, her mouth wide with full, sensitive lips. She uses no rouge or any sort of make-up. Her high forehead is framed by thick, pure white hair. Accentuated by her pallor and white hair, her dark brown eyes appear black. They are unusually large and beautiful, with black brows and long curling lashes. (p. 10)

Are we really to take this as a set of instructions for the producer? It’s as though O’Neill is having a pre-emptive tussle: no corset, no make-up, a face which doesn’t match the body. See if you can stage that. Stage directions are similarly specific throughout, often explaining how dialogue is to be played and leaving little leeway for interpretation. The lack of action in the play is another indicator that what is being attempted here is pure description, and it’s this which gives it its remarkable strength. We see a family which has fucked up. It’s nobody’s fault and everybody’s. James has an excuse for his miserliness, and this miserliness is the catch-all excuse for everyone else’s problems: Mary wouldn’t have ever taken morphine if it hadn’t been for the quack doctor James got in for her after Edmund’s birth; Edmund would stand a better chance of surviving TB if sent to a more expensive clinic; Jamie... well, Jamie’s a drunk and would probably be worse off without his father’s limited patronage, but this doesn’t stop him complaining about it. And complaining about it one minute doesn’t stop him from becoming lucid and affectionate the next. The characters do all care deeply for one another, but they just don’t do each other any good. This is the hook, and I was skewered.

No comments:

Post a Comment