Gertrude Stein – ‘Three Lives’

Somehow Christmas took me over, as it does many people, and all I read this month were a play, half a book on Israel, and Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives. The last book I gave up before the Israel one was a history book, Post War, not because it was bad but because it was long and after a while I noticed that most of it was lists concluding in a clause beginning ‘above all’. The Israel one – a novel – just had too many stories piled in there, and was the wrong place to go for someone who didn’t understand the historical foundation. Maybe I just don’t like serious books. Maybe language is what I’m after, more than content. Language that sends me. And who better to go to for that than Gertrude Stein?

Somehow Christmas took me over, as it does many people, and all I read this month were a play, half a book on Israel, and Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives. The last book I gave up before the Israel one was a history book, Post War, not because it was bad but because it was long and after a while I noticed that most of it was lists concluding in a clause beginning ‘above all’. The Israel one – a novel – just had too many stories piled in there, and was the wrong place to go for someone who didn’t understand the historical foundation. Maybe I just don’t like serious books. Maybe language is what I’m after, more than content. Language that sends me. And who better to go to for that than Gertrude Stein?

In tender hearted natures, those that mostly never feel strong passion, suffering often comes to make them harder. When these do not know in themselves what it is to suffer, suffering is then very awful to them and they badly want to help everyone who ever has to suffer, and they have a deep reverence for anybody who knows really how to always suffer, they soon begin to lose their fear and tenderness and wonder. Why it isn’t so very much to suffer, when even I can bear to do it. It isn’t very pleasant to be having all the time, to stand it, but they are not so much wiser after all, all the others just because they know how to bear it. (p. 320)The chances are you can work out from this extract alone whether or not you like Gertrude Stein, because she is all about language like this. Language which discusses in the simplest terms the reasons why people behave as they do, and feel as they do. There is a lot of repetition, because the behaviours and the people described are not consistent, so many fractionally differing truths need to be simply recorded, before the more complex amalgam can emerge. This way, complex language never needs to be used in order to describe it.

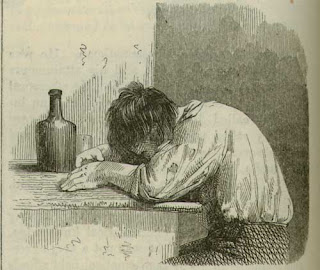

Three Lives, like Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, is based on an earlier book, in this case Flaubert’s Three Tales. This time I didn’t read the earlier book first, so I may have missed something, even most things, about the adaptation (if that’s the word for the book of the book). It takes the form of three separate stories, all set in Bridgepoint (based on Baltimore, the introductory essay tells us), and all concerning poor women. The structure is symmetrical, down to the stories’ titles: The Good Anna, Melanctha and The Gentle Lena. Good and gentle Anna and Lena work as maids (which gives them a satisfaction approaching happiness), and their stories are relatively short. Melanctha doesn’t work, or if she does it is not mentioned, and her story is longer than the other two combined. Anna and Lena are German immigrants, Melanctha is black. All three women are unfortunate to some degree. Two are fiercely independent; Lena barely has a mind of her own.

The strongest and also the most frustrating story is ‘Melanctha’. The majority of it consists of conversations between Melanctha and Jeff Campbell, as they to and fro in their love, always trying to ascertain what the other is feeling and why. Since the speech Stein writes is even more babyish than the surrounding prose, this gets wearing in places (I didn’t find that this was a problem in the shorter stories). Here’s Melanctha:

When you want to be seeing how the way a woman is really made of, Jeff, you shouldn’t never be so cruel, never to be thinking how much she can stand, the strong way you always do it, Jeff. (p. 250)She makes a fair point, and you can hear the panic in her voice. It is scarcely realistic: no-one would speak like that, no matter how sloppy their grammar. Rather, it is another expression of the possibilities present in this situation, the love between Melanctha the spontaneous woman, and Jeff the cautious man. Take the fragment ‘how the way a woman is really made of’. This offers in it three possible statements: ‘how a woman is made’, ‘the way a woman is made’, and ‘what a woman is really made of’. There are only two senses here – the first two mean the same thing. It’s difficult not to think, given Stein’s interest in Cubism and her appearance in Picasso’s famous 1906 portrait (Three Lives came out in 1909), that she is attempting the verbal equivalent: to show many sides of the same situation simultaneously – or as simultaneously as a time-based art form like fiction will allow. She doesn’t do this to show off, but because love is like that: when Jeff gets on his high horse, threatens to leave, puts his arms around her, says he still means all he said, it is inconsistent, but realistic. People have reactions to their own actions, and what they see as the likely consequences. They react based upon one set of circumstances, and change them in doing so, giving them something new to react to. Melanctha and Jeff tie themselves up in knots of loving, doubt, suspicion, understanding, misunderstanding, and ultimately it is all too much: by stages their love comes apart.

(Quotations from the Green Integer edition, 2004)